Almost two years after first being announced, and following two public consultations, two Senate committee reviews, and some 93 amendments along the way, the Treasury Laws Amendment (Making Multinationals Pay Their Fair Share – Integrity and Transparency) Bill 2023 (the Bill), which introduces the new earnings-based thin capitalisation regime, was finally passed by Parliament on 27 March 2024 and received Royal Assent shortly thereafter on 8 April 2024.

Scope

The new thin capitalisation regime will apply to ‘general class investors’, the definition of which consolidates the former concepts on inward and outward investors and excludes ‘financial entities’ and authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADI), to which the existing asset-based rules continue to apply. Australian plantation forestry entities will also continue to be subject to the existing asset-based rules. The regime will generally have retroactive effect, applying to income years commencing on or after 1 July 2023.

The new debt deduction creation rules will apply in relation to assessments for income years commencing on or after 1 July 2024 in relation to relevant debt arrangements entered into both prior to and after this date.

General Operation

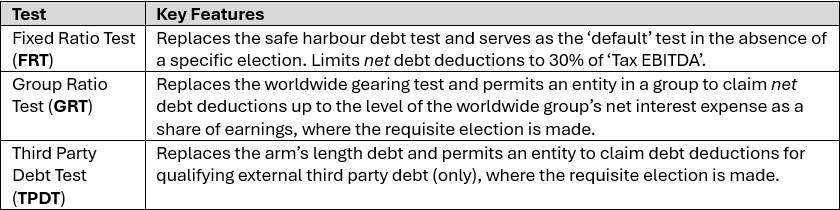

The new thin capitalisation regime comprises the following three tests:

Existing exemptions such as the de minimis threshold for associate-inclusive debt deductions of $2 million and the 90% Australian assets threshold exemption (for outward investing entities) will be retained.

The specific operation of each of the three tests is considered in further detail below.

FRT

As mentioned above, the FRT disallows debt deductions to the extent net debt deductions exceed 30% of ‘Tax EBITDA’.

Calculating Tax EBITDA

The starting point for calculating an entity’s Tax EBITDA is its taxable income or loss for the income year, disregarding the operation of the new thin capitalisation regime, except the debt deduction creation rules). The following amounts are then added:

- Net debt deductions1

- General deductions that relate to forestry establishment and preparation costs (unless they relate to the clearing of native forests) and amounts deductible under section 70-120 (capital costs of acquiring trees)

- Division 40 depreciation deductions (except insofar as immediately deductible, such as certain depreciating assets first used for exploration or prospecting for minerals)

- Division 43 capital works deductions

- Excess Tax EBITDA transferred from 50% controlled entities (see below)

Special rules apply with respect to the deduction of prior year losses (i.e., where a choice has been made under section 36-17 of the ITAA 1997), the subtraction of notional R&D deductions, as well as the subtraction of the following amounts from the foregoing calculation:

- Franking credits included in assessable income under Division 207 of the ITAA 1997; and

- Dividends, partnership distributions or trust distributions received from an ‘associate entity’2.

Excess Tax EBITDA

As intimated above, where certain entities have net debt deductions of less than 30% of their Tax EBITDA (i.e., excess Tax EBITDA), they may transfer such excess Tax EBITDA to their controlling entity. The relevant preconditions are:

- Both the controlled entity and controlling entities are Australian entities and use the FRT; and

- The controlling entity has a ‘direct control’ interest of at least 50% in the controlled entity.

15 Year carry-forward of FRT denied debt deductions

To the extent deductions are disallowed under the FRT, the disallowed deductions may be carried forward and claimed in subsequent income years, for up to 15 years, subject to continued use of the FRT and the application of modified loss recoupment rules.

GRT

The GRT can be used as an alternative test to the FRT and may benefit entities belonging to highly-leveraged groups by permitting them to deduct net deductions in excess of the amount permitted under the FRT, based on a ratio that relies on the group’s financial statements.

The GRT requires an entity to determine the ratio of its group’s net third-party interest expense to the group’s EBITDA for an income year, subject to a number of prescribed adjustments such as the removal of interest paid to and received from ‘associate entities’3 that are not part of the relevant group, and to disregard entities with negative EBITDA.

The GRT calculation can be complex for group’s with a large number of consolidated entities.

For the avoidance of doubt, there is no ability to carry forward debt deductions denied under the GRT, and application of the GRT requires a specific election to be made.

TPDT

Where the TPDT applies for an income year, an entity’s debt deductions will be denied to the extent they exceed its ‘third party earnings limit’ for the income year, which is the sum of each debt deduction of the entity attributable to a debt interest issued by the entity that satisfies the ‘third party debt conditions’ in relation to the income year.

Broadly, the ‘third party debt conditions’ are:

- The debt was issued to, and not held by, an ‘associate entity’4 ;

- Disregarding minor or insignificant assets, the lender has recourse only to Australian assets (excluding certain guarantees, security and credit support) of the entity, an Australian entity that is a member of the borrower’s ‘obligor group’, or Australian assets that are membership interests in the borrower;

- The debt is used to fund the commercial activities on the entity in Australia; and

- The entity is an Australian entity.

Special rules exist to provide for conduit financing (i.e., where a group member borrows from an external third party and on-lends to another group member) in limited circumstances.

For the avoidance of doubt, there is no ability to carry forward debt deductions denied under the TPDT. Whilst application of the GRT generally requires a specific election to be made, an entity will be deemed to have made such an election for an income year where it:

- Is a member of an ‘obligor group’ in relation to a debt interest where the issuer of the debt interest is an ‘associate entity’ has made a choice to use the TPDT; or

- Has entered into a cross-staple arrangement with another entity or entities, and one or more of those entities hade made a choice to use the TPDT.

Debt Deduction Creation Rules (DDCR)

Also included within the Bill are DDCR, which were a late addition and effective compromise in response to the proposed amendment of section 25-90 to not allow a deduction for interest expenses incurred to derive NANE dividend income, which was ultimately not proceeded with.

The DDCR will apply to both pre-existing arrangements as well as new arrangements entered into after the commencement date, and to all taxpayers subject to the thin capitalisation rules, except:

- Entities that qualify for the associate-inclusive $2 million debt deduction ‘de minimis’ exception;

- Entities that use the TPDT (on the basis that such entities are already subject to the third party debt conditions);

- ADIs;

- Securitisation vehicles; and

- Certain entities that are insolvency-remote special purposes entities.

Third party debt arrangements will also be excluded from the operation of the DDCR by virtue of the related party debt deduction condition.

The DDCR will fully deny debt deductions incurred in connection with the following two types of arrangements:

- Related party debt used to fund the acquisition of a CGT asset or a legal or equitable obligation (e.g., management fee obligation) from an associate (Type 1); and

- Related party debt used to fund certain payments and distributions to associates (Type 2).

Excluded from in-scope Type 1 arrangements are the acquisition of:

- Newly-issued membership interests in an Australian entity or a foreign company;

- Certain new tangible depreciation assets that are expected to be used for a taxable purpose within Australia within 12 months (i.e., to facilitate the bulk acquisition of tangible depreciating assets on behalf of associates); and

- New debt interests issued by associates (i.e., to ensure mere related party lending by an Australian taxpayer is not caught by the DDCR).

Notable, there is no exemption for the acquisition of trading stock.

Payments and distributions to associates will only fall under Type 2 where they are a:

- Dividend, distribution or non-share distribution;

- Distribution by a trustee or partnership;

- Return of capital, including a return of capital made by a distribution or payment made by a trustee or partnership;

- Payment or distribution in respect of the cancellation or redemption of a membership interest in an entity;

- Royalty, or a similar payment or distribution for the use of, or a right to use, an asset;

- Payment or distribution that is wholly or partly referable to the repayment of principal under a debt interest if the debt was used to make a payment or distribution that would have fell under Type 2;

- Payment or distribution of a kind similar to a payment or distribution mentioned in the preceding bullet points; and

- Payment or distribution prescribed by yet-to-be-made regulations.

The DDCR will require taxpayers to trace the use of related party loans to satisfy a burden of proof that they were not used for Type 1 or Type 2 arrangements. This could be burdensome for taxpayers with long-standing debt arrangements or cash-pooling arrangements.

The DDCR also contain a specific anti-avoidance rule that applies where the Commissioner is satisfied that a principal purpose of a scheme was to avoid application of the DDCR.

Transfer Pricing Interaction

Critically, whereas under the former rules the thin capitalisation regime was afforded primacy in the determining an entity’s quantum of debt, an amendment to section 815-140 of the ITAA 1997 places the thin capitalisation rules in the driving seat going forward. Effectively, the arm’s length conditions will now need to be assessed from a transfer perspective with respect to not only the applicable interest rate, but also the quantum of debt. Further information this regard can be found in the following previous Tax Insight from RSM Australia: Thin Capitalisation Reforms: Transfer Pricing Prevails in Determining Company Debt Amount

RSM Observations

The fact that the new thin capitalisation regime has, for many taxpayers, been enacted only months prior to the income year to which it applies, leaves precious little room to manoeuvre. Taxpayers with a 30 June year-end have less than 8 weeks to restructure their debt arrangements where this is appropriate.Highly leveraged operations are potentially the most affected by these rules. All taxpayers should take tax advice and at a minimum build a new thin capitalisation model. We expect the 2024 tax return forms will require disclosure of the thin capitalisation method chosen and applied.

Taxpayers now have an obligation to trace and document the use of all related party loans to assess whether they are used for ineligible debt creation purposes. Taxpayers could consider using working capital generated from operations (rather than related party loans) for ineligible debt creation purposes. The DDCR will be a key issue in corporate M&A transactions going forward.

Taxpayer’s who are subject to an audit will need to satisfy their auditor that their interest expense does not give rise to a permanent tax difference. The audit completion time-frame will bring forward the required tax analysis.

Withholding tax still applies to non-deductible interest paid to a non-resident.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

If you would like to learn more about the topics discussed in this article, please contact your local RSM office.

[1] Per subsection 820-50(3) of the ITAA 1997, the term ‘net debt deduction’ broadly refers to the sum of an entity’s debt deductions for an income year, less amounts included in the entity’s assessable income for the same period that is interest, or in the nature of or economically equivalent to interest, as well as certain other prescribed amounts.

[2] For the purposes of calculating an entity’s Tax EBITDA, an ‘associate entity’ will be an entity in which the other entity has a ‘TC control interest’ of 10% or more.

[3] For the purposes of applying the GRT, an ‘associate entity’ will be an entity in which the other entity has a ‘TC control interest’ of 20% or more.

[4] An entity will be an ‘associate entity’ of another for the purposes of the ‘third party debt conditions’ where there is a TC control interest of at least 20%, except where considered in the context of certain credit support rights, in which case a TC control interest of at least 50% represents the relevant threshold.